|

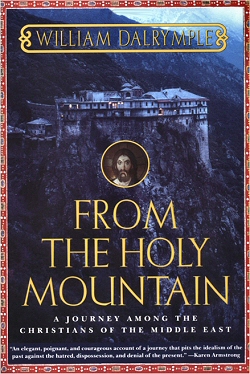

From Holy Mountain:

A Journey Among the Christians of the Middle East

William Dalrymple, a Scottish journalist, details his visit to the dwindling

Christians in the Middle East. The author follows the steps of John Moschos, a

sixth century Christian monk, who visited the entire Byzantine world during a

time when Christianity was the dominant religion of the region. The author

discovered the remnants of ancient monasteries and churches, which have survived

despite hostile environments. Dalrymple’s journey takes him to the Suriani

(author’s term for the Assyrians) of eastern Turkey, the ruins of Beirut, as

well as the Christians of Israel and Egypt. The book is a fascinating story of

the struggle in the Middle East to keep the ancient Christian flame alive. A

blend of history, spirituality and politics provides a perspective for

understanding the stories of persecution, intolerance, devotion and love.

William Dalrymple, a Scottish journalist, details his visit to the dwindling

Christians in the Middle East. The author follows the steps of John Moschos, a

sixth century Christian monk, who visited the entire Byzantine world during a

time when Christianity was the dominant religion of the region. The author

discovered the remnants of ancient monasteries and churches, which have survived

despite hostile environments. Dalrymple’s journey takes him to the Suriani

(author’s term for the Assyrians) of eastern Turkey, the ruins of Beirut, as

well as the Christians of Israel and Egypt. The book is a fascinating story of

the struggle in the Middle East to keep the ancient Christian flame alive. A

blend of history, spirituality and politics provides a perspective for

understanding the stories of persecution, intolerance, devotion and love.

The visit to Turkey records the extreme hardship that Assyrian Christians face in this hostile land. The Suriani are fearful and reluctant to speak with Dalrymple. The visit to Edessa (Urfa), the first city outside Palestine to accept Christianity, reveals that there are no functioning churches. In Diyarbaker, there are reportedly only a handful of Christian Armenians left. The author notes that from 200,000 Assyrians in the last century only 900 remain including a dozen monks and nuns in five monasteries in Tur Abdin in eastern Turkey. One village with an astonishing 17 churches now has only one inhabitant, its elderly priest. The people are caught in the crossfire between the government and the Kurdish fighters of PKK.

The journey to Syrian reveals a more tolerant society compared with the hostile atmosphere in eastern Turkey. Many Christians, both Assyrians and Armenians, who were driven out of Turkey and Iraq, have found a safe sanctuary in Syria. Even in Syria, there have been periods of anti-Christian sentiment. According to the author, during the 1960’s a quarter of a million Christians left Syria for other lands. It is noted that Qamishli is 75% Christian; and Touroyo, the modern Aramaic of Western Assyrians, is the primary language. The focus of the author is definitely on Orthodox Syrians. There are only brief references to recent Assyrian refugees from Iraq. The large Assyrian settlement of the 1930’s in the Khabur and Qamishli areas are not mentioned at all.

The chapter on Lebanon details attempts by Maronite Christians to maitain their status as dominant players in the country despite the increasing population of Moslems and other groups, and the internal, violent feuds between Christian political rivals. Despite the end of civil war, Christians still appear to emigrate due to anxiety over their future.

The Christians in Israel are also a dwindling minority, Dalrymple notes. In 1922, 52% of the population of the old city of Jerusalem was Christian. Now Christians comprise a mere 2.5% of the city’s population. There are now more Jerusalem-born Christians in Sydney, Australia than in Jerusalem. The Christians now make up less than 0.25% of the population of Israel and the West Bank, in contrast to a population of about 10% in 1922. What will happen to Christian shrines without the indigenous Christian population? As the Archbishop of Canterbury recently warned, the area, “ once a center of strong Christian presence”, risks becoming “ a theme park “, devoid of any Christians at all within 15 years.

The author concludes his trip by visiting the Coptic community of Egypt. Rising Islamic fundamentalism and violent attacks on local churches have intensified, causing an increased feeling of insecurity among the Christian population. They believe the government has ignored past attacks on Christians by Moslem fanatics until Moslems started attacking foreign tourists. Despite the large population (Copts make up at least 17% of the Egyptian population), there are few Christians in high positions within the government. As the result of this discrimination, it is estimated that about 500,000 Christians have left the country in the last ten years.

It is ironic that Christians are disappearing from the area where Christianity first began about 2000 years ago. The only way to stop this migration is to address the causes of a decline in the Christian population. Christians will not stop leaving until discrimination against them is halted and they are no longer fearful of their future in the area. It is probably too late for the Christians of Turkey and Israel, but future changes will determine whether or not other Christian communities in the Middle East will survive.

History Forum

History Forum 1900-1999 A.D. Assyrian History Archives

1900-1999 A.D. Assyrian History Archives