100 Years of Genocide,

|

|

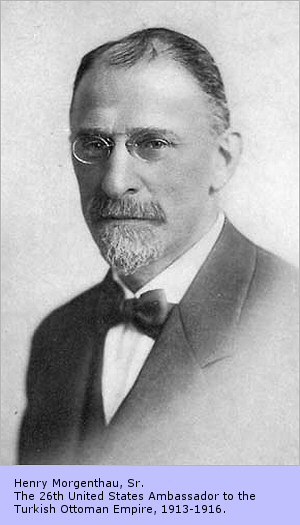

| Ambassador Morgenthau's Story (PDF, 15 MB) |

The Western Front

According to journalist Robert Fisk in his article, “The First Holocaust,” U.S. diplomats were among the first to record the Armenian genocide. Leslie Davis was the American consul in Harput at the time and wrote an account of seeing “the remains of not less than ten thousand Armenians” around Lake Goeljuk. Germans, too, who had been dispatched to Turkey to help organize the Ottoman military, reported mass slaughters and even more abominable acts. In the United States itself, The New York Times first began reporting of Armenian rapes and exterminations as early as November 1914. British diplomats across the Middle East, Fisk writes, received first-hand dispatches of the systematic slaughter. Private diaries of Europeans living in the region at the time exist and contain grisly and despairing passages of the event.

|

The West has known about this from the beginning. There is no disputing the fact that Armenians and other ethnic groups were massacred in Turkey in the early twentieth century.

In Turkey, however, it is effectively illegal to admit this. Today, Article 301 of the Turkish penal code prohibits citizens from insulting the Turkish nation or government. Even suggesting that the Turks of 100 years ago pursued an agenda of ethnic cleansing can be rewarded with death.

Journalists have been killed for writing about the genocide. In truth, writing anything in Turkey can be hazardous to one’s health. It ranks 154th in the World Press Freedom Index (out of 179 listed countries), and is currently “the world’s biggest prison for journalists.”

And because Turkey refuses to acknowledge the Armenian Genocide as a genocide, the United States, too, has remained mute on the subject.

From a legal standpoint, recognizing a genocide brings with it a host of complicated issues for a country - all of which perhaps pales in comparison to simply accepting blame for the planet’s most heinous criminal act. Turkey is a rare international ally for America - a Middle Eastern state that retains a non-violent relationship with Israel. For that reason, the United States has refused to officially recognize the Armenian Genocide. Doing so would be politically impolite.

This socio-political problem has transcended administrations and party lines. A resolution to recognize the Armenian Genocide was introduced by the 110th Congress in 2007, but then-President George Bush II publicly opposed it. Before succeeding the office, Barack Obama pledged that he would do what Bush could not. In 2006, Senator Obama criticized Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice for firing John Evans, the Armenian Ambassador at the time, “after he properly used the term ‘genocide’ to describe Turkey’s slaughter of thousands of Armenians starting in 1915.” Those are Obama’s own words.

“I shared with Secretary Rice my firmly held conviction that the Armenian Genocide is not an allegation, a personal opinion, or a point of view,” he added, “but rather a widely documented fact supported by an overwhelming body of historical evidence.”

In 2008, Obama reiterated his stance:

“America deserves a leader who speaks truthfully about the Armenian Genocide and responds forcefully to all genocides. I intend to be that President.”

In the six years since taking office, Obama has not been that President. He has refused to acknowledge the Armenian Genocide even once.

With Justice for All

I was not raised to hate Turks. As my mother would have it, I was not raised to hate anyone. But as I have grown up and learned more about the world and pursued my career in journalism, there is one prejudice that has been impossible to fight. I hate lies.

I hate any form of enforced ignorance that claims “2 + 2 = 5” and strikes down the indomitable voices that scream “4” until they’re silenced. By denying genocide, by denying the forced marches of Assyrians, of Greeks and of Armenians, by denying the tortures and the rapes, by denying the crucifixions and persecutions, Turkey is denying a final peace for so many. And they have been doing so for far too long.

My grandfather doesn’t think of himself as Armenian. He is a Bostonian first and a New Englander second, an American third and a businessman fourth. This fight for recognition is not his fight. This is not to say he bears no love for his father’s country; it is simply that time has moved on, America is now his home, its pledge the only allegiance he knows. The stories and the prayers of Kashador - or Kachador - and the traditions of the dead Nahigians are now a century extinguished.

What I’ve learned about Armenia has come from books, from fellow Armenians who have reached out, and from a diaspora that refuses to let the wax of its own dying candles cool. It wants what any culture wants, what any human deserves - and that is the truth.

My grandfather never wanted to be Armenian. But I am. And one hundred years later, I know how much that means.

About the author

Pierce Nahigyan is a freelance journalist living in Long Beach, California. His work has appeared in several publications, including Foreign Policy Journal, Intrepid Report, the Los Angeles Post-Examiner, New Internationalist and SHK Magazine. A graduate of Northwestern University, he holds a B.A. in Sociology and History.

Pierce Nahigyan is a freelance journalist living in Long Beach, California. His work has appeared in several publications, including Foreign Policy Journal, Intrepid Report, the Los Angeles Post-Examiner, New Internationalist and SHK Magazine. A graduate of Northwestern University, he holds a B.A. in Sociology and History.

Willful Blindness: Abraham Foxman and the Armenian Genocide

Willful Blindness: Abraham Foxman and the Armenian Genocide Armenian, Assyrian and Hellenic Genocide News

Armenian, Assyrian and Hellenic Genocide News